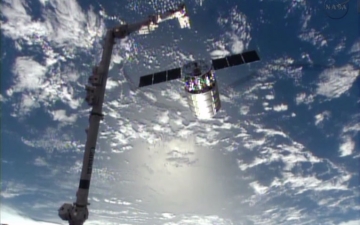

Cygnus Departs, ATV to Follow; When Will We Find a Better Way to Take Out the Trash?

At 6:31 AM CDT, astronauts aboard the International Space Station released Orbital Sciences Cygnus cargo vessel which has been berthed to the orbiting facility’s Harmony module for the last 23 days. Having been filled with trash and sent on its way, the Cygnus will enter Earth’s upper atmosphere in a destructive re-entry on Wednesday. With a successful departure, NASA and Orbital Sciences will review the final mission details, and officially draw the groundbreaking Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program to a close. OSC will join SpaceX, which has already been to the Station and returned, three times, as example of what can be accomplished under the type of public/private partnerships pioneered as part of the COTS program.

Much will be made of the stunning success of COTS, and much should; two new launch vehicles, two cargo vessels, one of which is an emergency escape and plug and play life support system shy of being a fully re-reusable crew transportation craft, two new launch pads, and all for less than NASA is spending this year for the Orion spacecraft alone. What should be readily apparent to all, is that if the public sector wants to remain involved in space exploration, then future programs need to have much more in common with COTS and Commercial Resupply (CRS) than they do with other programs which look to the past more than they do to the future.

But are we really all that focused on the future?

On Monday, September 28th, the fourth unit of the first “visiting vehicle” developed under the station program, the European Space Agency’s Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) “Albert Einstein” will detach from the Station’s Russian Zvezda port and begin its own destructive re-entry over Pacific, scheduled to take place on November 3rd.

What a stunning waste of resources. Taken together, the ATV and Cygnus cargo vessels offer a total of almost 68 cubic meters of pressurized volume, 48 and 19.8 respectively. For comparison’s sake, it is a capacity more than four times greater than China’s first station, Tiangong-1 (not the somewhat larger, fictional Chinese station pictured in “Gravity”), which will follow its comrades into the drink sometime in the not too distant future.

The world, with the very notable exception of SpaceX, has gotten all too comfortable with the notion of throwing away some of the most expensive and complex pieces of technology that we currently build, i.e. launch vehicles, with every liftoff. NASA, at the urging of Congress, cannot wait to build an even bigger and more expensive launch vehicle, the Space Launch System, and throw it away too. Sadly, after all the effort to preserve the Shuttle orbiters in their respective museums, SLS is scheduled to burn through the entire stock of re-usable Space Shuttle Main Engines, leaving visitors the somewhat inauthentic experience of looking at clever, but nonetheless pale imitations of the real thing. If there is any consolation, maybe Jeff Bezos will recover what remains of the real items from the ocean floor.

While we are left to argue the merits of the SLS and expendable launch vehicles in general, they at least have the dignity of serving a purpose during the course of which they are inevitably and regrettably consumed. It is difficult to make the same case with the ATV’s, HTV’s and Cygnus vehicles which depart the International Space Station. (Again, it is not by coincidence that it was SpaceX which developed a recoverable and ultimately reusable answer in the Dragon spacecraft)

While it is common to discuss the arguments for developing reusable launch vehicles with the rhetorical question of how much would a trip from New York to Paris cost if we torched each 747 at end of the flight, the case of the visiting vehicles in some ways seems even worse, flying the plane back to New York empty, or more accurately on to its next destination, and then burning it.

Regardless of where we intend to go beyond LEO, or when we do, the presence of pressurized, habitable modules having overcome the difficulties and expense of launch and already in orbit, represents an almost invaluable asset the ongoing destruction of which suggests a lamentable lack of imagination, or confidence in the future, any future, for human space exploration.

It is more than a little ironic that entrepreneurial NewSpace companies such as Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources are hard at working trying to figure out a way to convert asteroids, in other words rocks, located in distant orbits, into valuable resources, at the same time the ISS program is throwing away tens of thousands of pounds of refined metals, wiring, tanks, solar panels and generally useful commodities every year. Even if never used for actual human habitation in the future, the departing visiting vehicles represent a treasure trove of materials which one suspects the same or other NewSpace companies could find a way of moving into safe preservation orbits until the right opportunity comes along. Quite frankly, if we don’t have that capability either now, or cannot project it in the very near future, it might be time to collectively crawl back down into the oceans and call it day. We probably don’t belong in space in the first place.

Surely there is a better way to take out the trash.

Ah, Stewart one of the few journalists who has the guts to say it like it is. If more journalists had the guts to say it like it is and confronted these politicians who forced the SLS on the nation and said over and over again and again, loud and clear, what a foolish waste of money SLS is, maybe they would become embarrassed enough to back down from their niggardly reasoned stubborness. I`m talking about what happened after the moon missions.

The moon missions might yet become the equivalent of the voyages of admiral Zheng He. Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government of China had sponsored seven naval expeditions, but after that, the voyages of the Chinese treasure ship fleets were ended.

I find this incredibly wasteful and distressing also Stewart. What a helpful article. I only wish more people were listening.